Balance

I've been thinking a lot about balance lately. It has been a background thread slowly developing, with three distinct step functions where it rose to the foreground.

I've been thinking a lot about balance lately. It has been a background thread slowly developing, with three distinct step functions where it rose to the foreground.

init_0: video game flow

step_1: scavenger hunts

step_2: infinite player board games

step_3: hackathon judging

Let's start at the beginning.

Video Game Flow

Subtle flex: I'm taking a master's course in computer science, which allows me to explore many fun subjects. I've always wanted to spend enough time on topics and let them tumble around in my head. My college years were a blur of last-minute studies and tons of exams—not ideal. So this semester, I'm studying Machine Learning (because why not) and Video Game Design (because of course!).

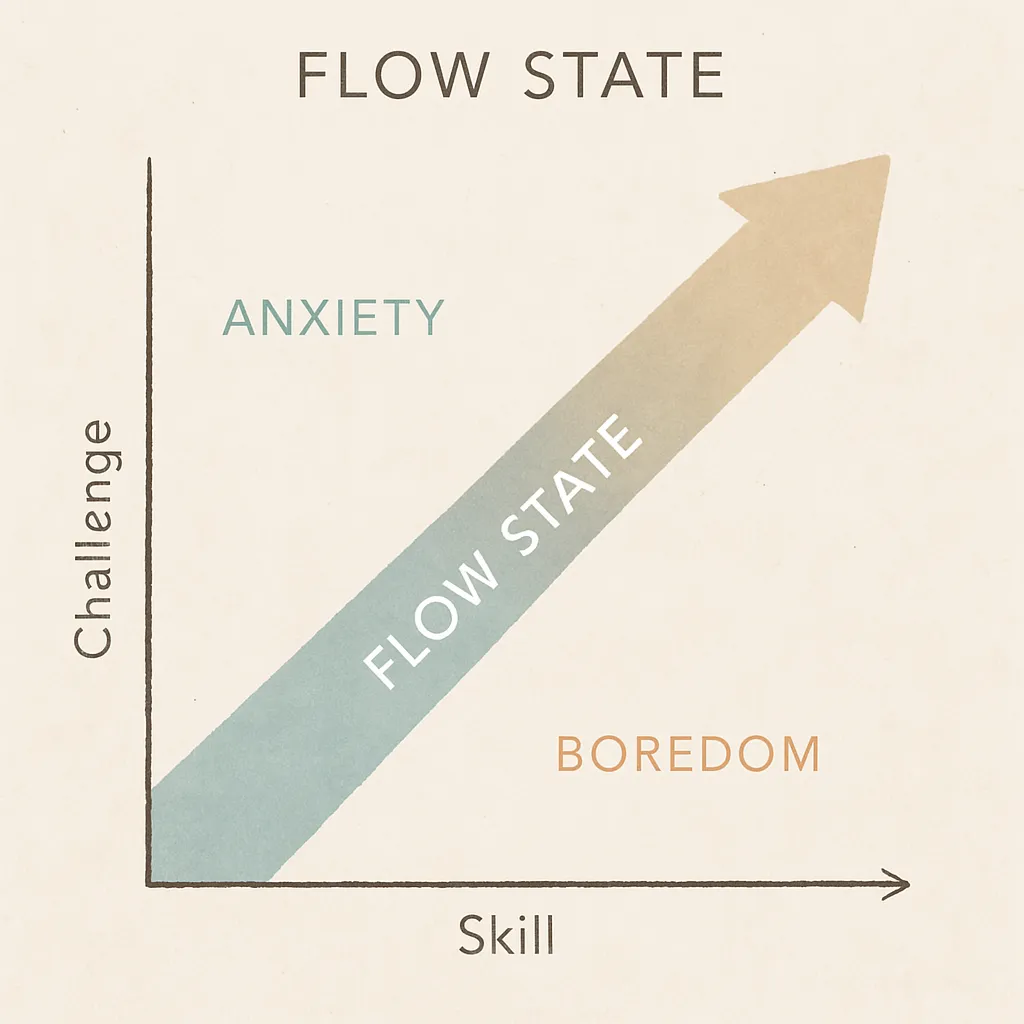

I've always been a fan of video games, so it's fun to revisit them from a creator's perspective. As designers, we must balance the subtle push and pull of keeping the game challenging but not frustrating, fun but not boring, and easy to learn but difficult to master. While building a multiplicative zombie survivor in Unity, our team is constantly tuning the game to be just right. We are currently play-testing, running surveys, and iterating.

Aside from that, learning about the history of video game evolution is a worthy nerd-snipe, and I strongly suggest that anyone interested in video games spend time tracing how we got here. It's incredibly fun!

The Purpose of a Scavenger Hunt

A friend of mine attended a team offsite where they played several social games, one of which was a scavenger hunt. An interesting observation: the purpose of a scavenger hunt is not merely to "win" it. That is the immediate goal, sure, but the overall goal is to have fun—collaborative, shared fun. If you reduce it to a purely competitive sport, some people win, but many more lose. In the end, the average "had-fun" quotient is lower than when it started.

A question then: Is a scavenger hunt a good party game, or just a good game for large groups of people?

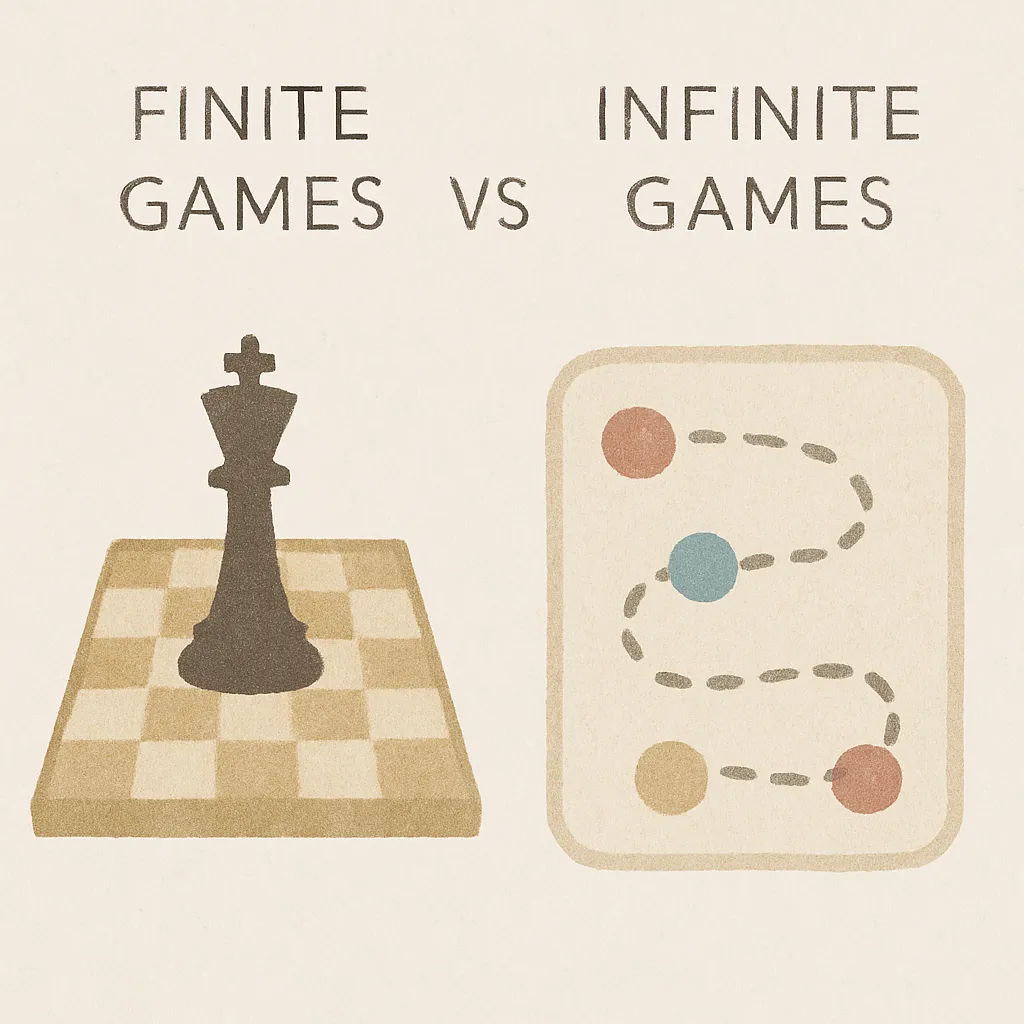

Infinite vs. Finite Games

James Carse distinguishes between finite and infinite games. Finite games are played to be won, with clear endpoints and victors. Infinite games are played to keep playing—the goal is to sustain engagement and pull more people into the experience.

My favorite board game is Ricochet Robots, where everyone simultaneously tries to solve the same spatial challenge. What makes it brilliant is that, although technically there is a winner each round (whoever finds the most optimal solution), everyone experiences the same puzzle, the same "aha" moments, and—importantly—everyone plays until the end. No elimination, no waiting while others finish. And an infinite number of people can play! This may just be the ultimate party game. The fun distribution is uniform for everyone, right until the end.

A thought then: Why do we accept game designs that result in diminishing engagement for a significant portion of participants? For party games, perhaps we should be playing infinite games rather than finite games. After all, maximizing fun is the goal, right?

Hackathon Judging

The student becomes the teacher. I became a hackathon judge.

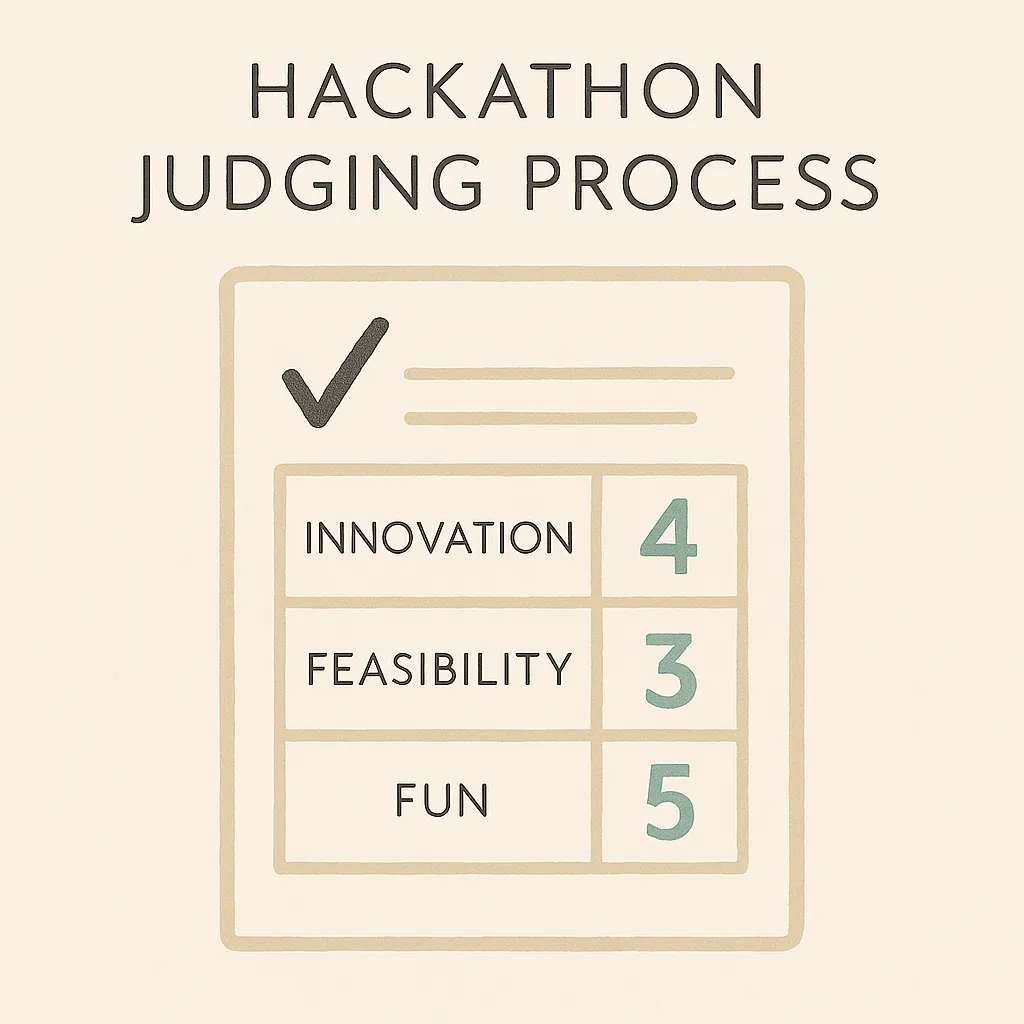

A while back, I returned to my college—about a decade later—to be on the jury panel for a hackathon. 24 hours of creative energy, and I got to witness the culmination of it all. How cool is that? But there were 60 teams and nine judges. To manage this, the organizers split the jury into three teams, each of which selected three top teams for the finals. We were given a rubric to score projects based on innovation, technical complexity, feasibility, and business impact.

At first, I was having too much fun talking to the teams, neatly overshooting the allocated five minutes per project. Eventually, the organizers pulled me aside and kindly asked me to hurry up. Fair. But I had an ulterior motive. I wasn’t just there to judge the students—I also wanted to motivate them. It's easy for students to attend a hackathon, have a bad experience, and be put off forever. Hackathons should be fun, and I wanted to ensure they felt that way. So, I spent extra time understanding their motivations, their solutions, and—whenever possible—offering constructive feedback for the future.

The problem was that the hackathon was designed as a finite game.

We were trying to reach the winners as fast as possible, so teams were split among different judges. This meant I saw only a third of the projects. What happens when the best projects my group saw are not comparable to the best ones seen by others? Because that is exactly what happened. And we didn't (or couldn't, given the time constraints) solve it.

This issue was exacerbated by the rigid rubric. Some jury teams strictly followed it and aggregated scores, which led to some projects missing the finals due to poor weight calibration. Meanwhile, my team took a more holistic approach—we judged projects based on innovation, technical capability, and the experience of the team members. The last part was crucial because we wanted to keep this as close to an infinite game as possible. For instance, some impressive hacks by first-year students clearly deserved a shoutout.

The results were predictable: some truly creative, scrappy hacks lost out to polished but uninspired CRUD applications that happened to tick all the rubric boxes. By trying to be objective, we inadvertently privileged certain types of projects. As Jon Gottfried wisely notes, "Being the 'best' is an entirely subjective assessment that varies from person to person and from event to event."

I might be wrong—maybe having vague selection criteria is a bad idea. But I couldn't shake the feeling that the process was ultimately more unfair than fair. I saw the emotional aftermath: three elated winning teams and the rest with varying degrees of disappointment. The fun distribution was severely unbalanced.

I scribbled personalized feedback for each team I judged—small notes of appreciation for specific impressive elements. Their reactions—genuine smiles, thoughtful nods—suggested it mattered. They walked away with something beyond binary victory or defeat.

Rethinking Hackathons

What would hackathons look like if we designed them with collective experience as a primary metric? Perhaps multiple recognition categories to acknowledge different forms of excellence. Maybe structured feedback mechanisms to ensure every participant walks away with something valuable. Or progressive judging formats that reduce the impact of any single evaluator’s preferences.

What if we judged hackathons more like how Anson Yu describes finding "sparkly" people — those with a "joie de vivre mixed with a dedication to craft, lightly encased in wit"? What if we valued:

- Normalized kindness – How participants treat teammates and competitors, regardless of skill level.

- Callback ability – The mental agility to connect ideas quickly.

- Consistency of creativity – Regular output that shows dedication to craft.

- Default peace – The willingness to embrace ambiguity and confusion.

The goal isn't to eliminate recognition for excellence—it should be celebrated. Rather, it’s about expanding our definition of what deserves recognition and designing systems that acknowledge the spectrum of achievements in creative endeavors.

These thoughts on balance continue to evolve. They are reshaping how I approach game design, event organization, and evaluating others’ work. The pertinent question for me: In any system involving multiple people, how do we maximize the total positive experience while maintaining meaningful differentiation? How do we design experiences that allow everyone's unique "sparkle" to shine?